Schools that keep teachers

By IOE Editor, on 23 March 2020

By Dr. Sam Sims

Four in ten secondary headteachers in England report that a shortage of qualified teachers is hindering the quality of instruction in their school. This is not due to declining recruitment. If anything, the number of entrants to secondary initial teacher training has followed a slight upward trend in recent years. Rather, the problem has been keeping them: since 2011, each new trainee cohort has left the profession at a faster rate than the last.

Three years ago, Becky Allen and I noticed wide variation in the retention rates of newly qualified teachers (NQTs) across schools. We hoped this would help us identify which types of schools struggle to keep new teachers. Perhaps those located in areas with many alternative employment opportunities? Or those with lower Ofsted grades? Or those with more disadvantaged pupils? To our surprise, however, there were no clear differences visible in the data. So what is different about the schools that keep teachers? The evidence suggests that it is something local to each school – the extent of staff collaboration, for example. In any case, it seemed likely that rich teacher survey data would be required to pin it down.

Several such studies had been conducted in the US, all of which had contributed to our understanding but none of which were entirely satisfactory. Some used the Schools and Staffing Survey, which included a representative sample of teachers but provided only patchy information on subsequent retention. Others used state-wide surveys linked to government data on retention. However, these provided school-average, rather than teacher-level data. Still others used survey data from New York City but were unable to distinguish a teacher leaving the city from a teacher leaving the profession overall. I also investigated this question using the 2013 Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) data but was forced to rely on teachers’ self-reported intentions of leaving.

Fortunately, when the most recent wave of TALIS data was collected in England in 2018, teachers were given the option to consent to their questionnaire responses being linked to the School Workforce Census. Around three quarters did so. As a result, we now have representative teacher-level data including rich survey measures of the school working environment and objective information on whether or not teachers remain in the profession.

John Jerrim and I have just released a paper using this new data to investigate what distinguishes schools that keep teachers. We boiled down 26 variables from the TALIS questionnaire into five overall measures of the school working environment – leadership/management, workload, collaboration, discipline and appropriate teaching assignments – and then investigated the relationship between each of these and retention. In short, we found schools that keep teacher are distinguished by having more supportive leadership and better standards of discipline.

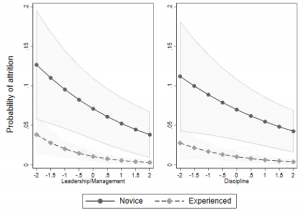

The chart below plots the relationship between these two working conditions and retention, holding constant other working conditions and teacher characteristics. The vertical axis shows the probability that a teacher is no longer working in any state-funded school in England in the subsequent academic year (0.15 indicates a probability of 15%). The horizontal axis shows the overall score for the two working conditions, based on teachers’ survey responses. A score of zero is equivalent to the average score across all teachers and a score of plus (minus) one is equivalent to one standard deviation above (below) the mean. The black line shows the relationship for novice teachers (less than five years of experience) and the grey lines for experienced teachers.

Notes: Shows the predicted probability of attrition by the subsequent academic year for a teacher with otherwise average characteristics. N=1,953 primary and lower-secondary teachers. Shaded regions show the 90% confidence interval.

The left-hand panel shows that teachers who report higher Leadership/Management scores for their school are considerably less likely to leave the profession. Indeed, for an experienced teacher with otherwise average characteristics, a one standard deviation increase in the Leadership/Management score is associated with a fall in the probability of leaving the profession from around 1% to around 0.5%. For a novice teacher with otherwise average characteristics, the same increase in Leadership/Management score is associated with a decrease in the probability of leaving the profession from 7.1% to 5.2%. Interestingly, we find that the Leadership/Management score also predicts teacher job satisfaction and whether they remain in their specific school.

Discipline – shown in the right-hand panel – has a very similar relationship with attrition. Moving an experienced teacher from the mean to one standard deviation above the mean on the Discipline score is associated with a fall in the probability of leaving the profession from around 1% to around 0.5%. For a novice teacher with otherwise average characteristics, the same increase in the discipline score is associated with a decrease in the probability of leaving the profession by the next academic year from 7% to 5.4%. We also found that Teachers who report better Discipline scores for their school are more likely to stay working in their specific school.

So, what should schools do to keep their teachers? The Leadership/Management score is composed of a number of questions capturing whether there is a supportive culture within the school, whether leaders recognise teachers for doing a good job, whether teachers have a chance to participate in decision making and whether teachers are given the autonomy necessary to do their job. The Discipline score is composed of questions relating to whether staff in the school consistently enforce behaviour standards and the extent to which they experience verbal or physical abuse. The data shows that schools differ quite considerably in their average Leadership/Management and Discipline scores, suggesting that many schools could benefit by prioritising improvements in these areas.

You can read the full paper, including details on our methods here.

Close

Close